Hate-speech law ‘threatens learning’ – and commerce

by - 30th March 2016

A COLONIAL-ERA hate speech law is destroying freedom of expression across South Asia.

Its critics have spoken to Lapido after Indian cricket captain Mahendra Singh Dhoni, received a warrant for his arrest in January for allegedly failing to appear to answer charges in connection with marketing his products on the front page of a business magazine, in the guise of Vishnu, one of Hinduism’s foremost gods.

Dhoni received a non-bailable warrant on 8 January this year, issued by the court in Anantapur in the south Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, after he failed to present himself to the court despite earlier summons.

When the original warrant was issued Dhoni was on a cricket tour of Australia. He took up the matter with the Supreme Court, which stayed the warrant. This repeated a similar order in September 2015 when the SC stayed the criminal proceedings against him on the complaint lodged but this time in a different state, Karnataka.

The SC has adjourned the case until 12 May.

Raj

Section 295A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), first introduced by the British Raj in 1927, outlaws the ‘deliberate and malicious . . . outrage of religious feelings’

Punishment is up to three years’ imprisonment and/or a fine.

Dhoni, revered icon of Indian cricket, received a non-bailable warrant in January this year in Section 295A case, in connection with a charge of allegedly hurting Hindu sentiment.

‘Any class of citizens of India’ is protected against ‘insults or attempts to insult the religion or the religious beliefs of that class’ says the century-old law.

Yet, under the rubric of ‘hurt to religious sentiment’, religious communities, cults and sects are using the law to stifle criticism of any religious behaviour across the whole of South Asia, it’s claimed, and undermining freedom and reform.

After 1947, when colonialism ended and the subcontinent split into different nation-states, India, Pakistan, Burma, Sri Lanka, and later Bangladesh continued to use some form of the IPC, and retained Section 295A.

Hurting

Sanal Edamaruku, an Indian ‘rationalist’ – as they are known – has been living outside India since 2012 after he received death threats, and had several cases registered against him for hurting the religious sentiments of Catholics.

In April 2012 he exposed how the water dripping from a statue of Jesus Christ in a church in Mumbai, promoted by the Catholic Church as a ‘miracle’, was only a case of bad plumbing.

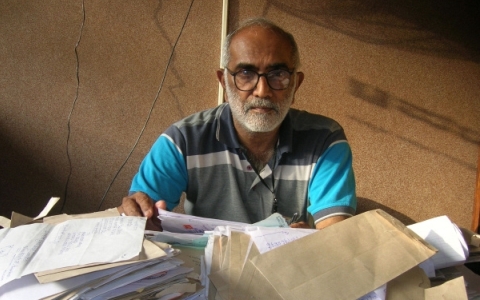

Now Narendra Nayak, the president of Federation of Indian Rationalist Associations (FIRA), has told Lapido how brave rationalists working to educate people against superstition and fake god-men have been ‘persecuted’ under the law.

‘The original intent of Section 295A was to restrict hate speech, but it is now used against rationalists to stop the work we do,’ he said.

Nayak adds that prosecutions are used as harassment, to the point of persecution. In India, appellants can file a case under Section 295A simultaneously in multiple courts, forcing the accused to run from one court to another to answer the charges.

‘Though these charges are hardly ever validated in the higher courts, by filing a complaint in multiple – sometimes up to 25 different – courts across the state or even the country, they frustrate the accused and try and sap the energy and will,’ says Nayak.

Censorship

Yet it is not only those hoping to stem superstition who face the law. The creative and the inquisitive are also targets.

The most extreme case of self-censorship in recent years, threatening learning and religious reform across South Asia was Penguin’s decision in February 2014 to withdraw and pulp all copies of Indologist Wendy Doniger’s book The Hindus: An Alternative History, after a case was registered against her under Section 295A.

History

Section 295A of the IPC is one of many under the chapter that deals with 'Offences Relating to Religion'. It is, however, a later addition to the original IPC of 1860.

The new section was introduced by the British administration to pacify Muslim anger after Mahashe Rajpal, a Hindu, published Rangeela Rasool (The Promiscuous Prophet) in 1924 – a controversial book about Prophet Muhammad’s personal life.

In the absence of a law that prohibited insult to religion, Rajpal was tried under Section 153A of the IPC, which prevents, ‘promoting enmity between different groups’.

However, the Lahore High Court in Rajpal v. King Emperor (1927) found that the book, while a ‘scurrilous satire’ did not ‘attack the Mahomedan religion as such or to hold Mahomedans as objects worthy of enmity or hatred’ and acquitted him.

This judgement exacerbated the already poor relations between Hindus and Muslims in northern India during the 1920s.

It was to diffuse these tensions that the National Assembly sought to amend the penal code and added Section 295A to prevent religious polarisation.

Hate speech

Critics argue the law is anachronistic and doesn’t reflect the needs of a modern democracy.

Yet apologists believe that Section 295A allows the state to act against hate speech and incitement of communal violence, especially against religious minorities.

On 28 February 2016, for instance, a case of hate speech was registered under Section 295A against the Union Minister of State for Human Resource Development Ram Shankar Katheria, for allegedly inciting Hindus to ‘pick up arms’ against Muslims.

Soli J Sorabjee,an Indian jurist and former Attorney-General of India, argues that there are enough legal safeguards within the constitution to protect informed criticism of religion.

He writes, ‘The [legal] yardstick is not the standards of hyper-sensitive and volatile minds but those of ordinary persons of normal sensibilities.’

Regardless of these assurances of fairness and justice, individuals who challenge religious dogma and superstition in South Asia continue to be harassed and threatened both in and out of court.

The recent murders of what, in India are called ‘rationalists’ and in the West ‘secularists’, across India and Bangladesh, and the use of the blasphemy law – in addition to Section 295A – in Pakistan, are all testament to the dangers now posed by religion itself in South Asia.

It is perhaps because of these limitations that Nayak repeats over and over again during the interview: ‘Section 295A does not have any role in a civilised society.’