ANALYSIS Easter Rising: religious sacrifice or campaign of terror?

by - 29th April 2016

ON THIS day 1916, the Easter Rising, a six-day armed insurrection in Ireland, ended with activist Patrick Pearse agreeing to an unconditional surrender. The Rising, or Rebellion as it was also known, was organized by Irish republicans in a bid to end British rule, secede from the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and create an independent Irish state.

Reflecting on events one hundred years on, Northern Ireland’s current Attorney General John Larkin says the Rising was ‘profoundly wrong.’

The history of Ireland is messy and contested. An act can be seen as a fight for freedom, a moment of treachery or both. For Larkin, a Catholic who was raised on the political writing and speeches of Patrick Pearse, the event was ambiguous.

In Catholic, nationalist Ireland Pearse was a powerful and iconic figure. Being exposed to these texts was important to Larkin’s education, though he viewed it as unwholesome.

‘Looking at 1916, you have individuals of huge moral worth, individuals capable of huge self-sacrifice, nonetheless doing something that was profoundly wrong.

‘It wasn’t justified in terms of any of the traditional Just War criteria - there was no mandate for it.

‘One of the ironies of history is that it is often referred to as the Sinn Fein rebellion… It couldn’t have been a Sinn Fein rebellion, the official policy of the party up until 1917 wasn't for a republic, but a monarchy on the Austro-Hungarian pattern.

‘The 1916 Rising was a product of a secret revolutionary society, and an adventure that lacked any democratic or constitutional legitimacy, however much one admires - and in a personal sense it is very difficult not to - the courage and the zeal for public welfare as they saw it, of many who took part in it.’

Garrison

The Attorney General points out that a number of people who ‘sacrificed’ their lives, did not do so through their own choice, including children. He refers to T.S. Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral in relation to the Rising - the temptation that is closest to real good is the most dangerous. ‘Merely because one uses the language of sacrifice for others, or evokes a certain language that may echo with Christian language and symbolism, doesn’t mean one is acting in a way that can be regarded as Christian.’

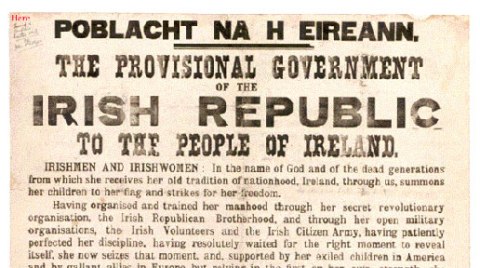

The Rising marked the return of 'physical force republicanism' to Irish politics. It began on 24 April 1916, Easter Monday, when twelve hundred volunteers seized strategic positions in Dublin, including what would become the headquarters garrison at the General Post Office. A Provisional Government proclaimed Ireland to be a Republic.

Public reaction in Dublin was initially mixed, and at times very hostile to those who participated in the Rising. Many families had loved ones fighting in the First World War at the time, and were not sympathetic to the Republican slogan that ‘England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity.’ For six days the Citizen Army and Irish Volunteers fought the Royal Irish Constabulary, the Dublin Metropolitan police, and the British Army. The fighting killed 508 people and wounded 2,520. When Patrick Pearse and his comrades surrendered on 29 April, they were jeered at and even spat on as they were taken off to jail.

After twenty months of slaughter on the western front, with hundreds of thousands of lives lost, the British wanted vengeance on those seen as traitors for attacking a country at war. They executed the leaders of the Easter Rising which sparked a shift in attitudes, creating resentment against perceived British brutality. Many were appalled to hear how James Connolly, unable to stand before the firing squad due to a broken ankle, was tied to a chair and shot in the yard of Kilmainham Gaol.

Foreigner

The history and writings of the main figures of 1916 make clear that it was no coincidence that they staged the Rising at Easter. The choice of date by Pearse was deliberate and the event is generally remembered on Easter Monday rather than 24 April each year.

At the end of Pearse’s best-known play, The Singer, the hero, MacDara, goes out to fight the Gall (an old Irish word meaning ‘foreigner’) – against innumerable odds - with these words: ‘One man can free a people as one Man redeemed the world. I will take no pike, I will go into the battle with bare hands. I will stand up before the Gall as Christ hung naked before men on a tree.’’

Thomas McDonagh, signed the original Proclamation and declared at his court martial hearing, ‘I go to join the goodly company of men who died for Ireland, the least of whom is worthier far than I can claim to be, and that noble band are themselves but a small section of the great, unnumbered company of martyrs, whose Captain is the Christ who died on Calvary.’

Irish Times columnist Fintan O’Toole summarized the religious theme in the following way:‘The founding act of the modern Irish State – the 1916 Rising – is a religious as much as a political act, and conceived by its leader, Patrick Pearse, as such. Its symbolic occurrence at Easter, its conscious imagery of blood sacrifice and redemption, shaped a specifically Catholic political consciousness that belied the secular republican aims of many of the revolutionaries.’

Reflecting theologically on the events of one hundred years ago, Attorney General John Larkin suggests, ‘The Proclamation invokes Almighty God, and it is plain from the context it is God the Creator, not a deistic figure. If you compare that to those who see themselves as the heirs of 1916 now, you don’t get anything remotely like the same theological framework.’

In his view, however mistaken in terms of moral judgment the rebels were, they were people who, for the most part, saw themselves as acting in faith. All the signatories of the Declaration died as believing Catholics who had, at the point of death, reconciled themselves to what was going to happen. How they did so is known only to God. They thought in terms of a Christian framework; and that, in the Attorney General’s view, is lacking from our current public discourse.

Ulster

Northern Ireland is in the midst of a decade of centenaries - this year the centenary of both the Rising and the Battle of the Somme are remembered. The story of Edward Carson’s Ulster Volunteers, who became the 36th Ulster Division and the sacrifice they made at the Somme, is indivisibly linked to the foundation of the Northern Ireland state. Though the Irish State wasn’t founded until 1922, as W.B. Yeats noted in his Easter 1916 poem, ‘All changed, changed utterly: a terrible beauty is born.’

Northern Ireland’s current political leaders have sought carefully to remember these events, while continuing the journey of reconciliation. Martin McGuinness wants to see the peaceful and democratic reunification of Ireland, and sees reconciliation as a step towards that. He has a ‘tremendous admiration for those who went out and fought in 1916’ to bring about the freedom of every sod of Ireland, as Patrick Pearse put it. He believes it was a just campaign in light of all that was going on at the time. But any attempt to use the events of 1916 to ‘make an argument for another campaign of a military nature is something I would totally reject.’

First Minister Arlene Foster’s reflections are influenced by the fact that her father, a part-time policeman, was attacked by the IRA. ‘For those of us living in Northern Ireland, the Easter Rising was used in a very negative way to justify a campaign of terrorism against fellow Irish people frankly. It’s obviously for me a negative event and something that was unjustified and something that was a very violent attack.’

Forgiveness

Northern Ireland has a peace process that is respected around the world. Politicians are now keen to see greater reconciliation, though there is little agreement as to how this would occur or what it would look like. Attorney General John Larkin surprised some with his comments on the issue. ‘Reconciliation is virtually impossible, save in theological terms. I don't think reconciliation is possible unless the divine command to forgive is acknowledged.’

He suggested that if you look at the matter in purely secular terms, a therapist may say it is not doing you any good to harbour these feelings and it is not harming your enemies so let’s get rid of the negative thoughts, but that is a very far cry from forgiveness. In purely secular terms, once you have spoken to a therapist, why would you forgive? Why would you not want to strike back?

‘In our context, reconciliation is incomprehensible in other than Christian terms.’

As Northern Ireland reflects on events from a hundred years ago, and those from its more recent troubled past, the views of Northern Ireland’s top legal advisor - that the Rising was profoundly wrong and that reconciliation is impossible without forgiveness - have caused many to pause and reflect.

Peter Lynas is a former barrister who works for the Evangelical Alliance. He recently interviewed First Minister Arlene Foster, Deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness and John Larkin, the Attorney General of Northern Ireland as part of a faith and reconciliation project www.100days100years.com