ANALYSIS Fixing the EU: is Christianity the key?

by - 29th June 2016

IN THE aftermath of the Brexit vote, Pope Francis has urged the European Union to return to its roots.

From an historical perspective, and arguably from the Pope’s viewpoint (even though he has not explicitly said so), these roots are, to a great extent, Catholic.

As the EU plunges into deeper turmoil, religion, therefore, may offer a clue to the way forward.

Earlier this year, Pope Francis stated that he wanted Britain to stay in the EU to help smaller countries and ‘make a stronger Europe’.

However, commenting on his way home from Armenia on the Sunday after the Referendum, he affirmed that the result was the ‘will of the people’, which, according to Catholic social doctrine, must be exercised and respected.

As reported in the Catholic Herald, he went on to express his desire to see Europe stay together. But he admitted that ‘something isn’t working in this unwieldy union’.

‘The European Union must rediscover the strength at its roots, a creativity and a healthy disunity, of giving more independence and more freedom to the countries of the union,’ he said as he prepared to fly home from Armenia on Sunday.

His fellow Catholic, Donald Tusk, President of the European Council (and former PM of Poland - the EU’s most Catholic nation), shares this view.

According to the BBC, in the weeks running up to the Referendum, Tusk had repeatedly warned that more centralization would turn citizens against the EU.

In an address on the 40th Anniversary of the European People’s Party (EPP - founded originally by Christian Democrats) at the end of May, Tusk said that, ‘obsessed with the idea of instant and total integration, we failed to notice that ordinary people, the citizens of Europe, do not share our Euro-enthusiasm’.

And he warned that a vision of a federation was not the best answer to what he called the ‘spectre of a break-up’ that was haunting Europe.

Neither the Pope nor Donald Tusk referred explicitly to the EU’s Catholic roots nor appeared to advance a Catholic line, at least in the above contexts. Indeed, unlike his predecessor, Pope Francis seems to have gone out of his way to avoid doing so.

But there seems little doubt that Catholic understandings and ideas are in the background of their thought.

Tusk has, in fact, on occasions indicated his own religious position. For example, referring to the migration crisis in Europe, he commented: ‘Christianity in public and social life carries a duty to our brothers in need’ and a ‘readiness to show solidarity and sacrifice’.

And in the same speech to the EPP, he quoted Pope John Paul II: ‘Solidarity is never one against the other. Solidarity is always one with the other, together’. And he added, not a little ironically: ‘When one is a Christian Democrat, it is sometimes worth listening to the Pope.’

Similarly, Pope Francis, addressing European leaders (including Tusk) at the Vatican in May this year, and referring also to the migrant crisis, chose to describe the roots of Europe as essentially dynamic and inclusive. ‘They have been consolidated down the centuries by the constant need to integrate in new syntheses the most varied and discrete cultures’, he said.

However, he declared, that the Church had a vital role to play, and not by being nostalgic for some past Christendom.‘Only a Church rich in witnesses will be able to bring back the pure water of the Gospel to the roots of Europe’, he said.

Witnesses

Neither Francis nor Tusk appears to be arguing that the future of the European Union lies in a religious revival in terms of personal faith and church affiliation.

But they are, it seems, contending that, for the EU to come through its present crises, it must jettison ideas of ‘ever closer union’ and a European super-state and recover the essence of its Catholic-inspired founding principles of solidarity and subsidiarity.

And, they imply, those who do profess Christian faith need to express it through practical and sacrificial service of others.

Relational

Several commentators in the UK also see an important role for Christianity in navigating the EU through its present woes.

Ben Ryan of Theos (himself a Catholic), argued in his pamphlet for Theos, A Soul for the Union, that the EU had lost its way and needed to rediscover its moral and Christian roots (again, solidarity and subsidiarity in particular). And in a paper for Cambridge think tank KLICE, that it should become ‘the moral force the 21st century world needs’.

Launching an online discussion on ‘re-imagining Europe’ last September, the Archbishop of Canterbury asked, 'How can we revitalise ideas such as sovereignty and subsidiarity – ideals formed out of Christian faith whose political dimensions capture their meaning only in part?’

All these commentators are essentially pressing for a recovery of Christian principles, though not necessarily of Christian faith.

Nevertheless, it can be argued, there is in their advocacy an implicit appeal to faith or ‘vestigial’ religion.

As Nelsen and Guth averred, in their study Religion in the European Union: the neglected variable: ‘A decline in traditional religion does not mean that religion no longer matters in Europe. Religion shapes cultures in deep and lasting ways. Individual worldviews, once shaped by understandings of God persist in more secular guises from generation to generation.’

Roots

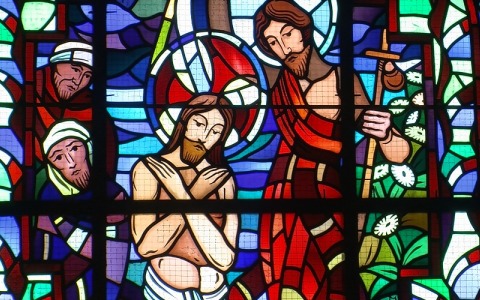

As well as the previous Pope Benedict, there are many others who have argued that the roots of Europe remain Christian, and that in any crisis people return to their Christian roots.

A particularly compelling (though probably little known) Portuguese-made documentary broadcast in 2013 examined the ‘Christian roots of Europe’, arguing that at heart the people of Europe remain Christian, and that Benedict, Francis and Ignatius who were lights that shone in Europe’s darkest days, are inspirations and guides still.

It remains to be seen, however, whether or not Europe’s implicit faith is sufficient to enable the recovery programme that is being urged by Catholic leaders.

Britain is, of course, on track to leave the EU, but is unlikely to be able just to watch events unfold from the sidelines. Developments in Europe will continue to impact the UK and vice-versa.

And it cannot wholly be dismissed therefore that Britain might wish at some time in the future to rejoin (and be welcomed into) a new transnational European entity, but reformed along the lines that gave it birth.

Related links:

Still time to face facts on Europe

Christians looked to the Bible for voting decision

Peter Carruthers is a writer and strategic analyst and is Director of Vision 37 Ltd which helps organizations understand themselves and their constituencies. He is a co-founder of the Farming Community Network.

Peter Carruthers is a writer and strategic analyst and is Director of Vision 37 Ltd which helps organizations understand themselves and their constituencies. He is a co-founder of the Farming Community Network.