ANALYSIS: The revival of Sikh nationalism begins to worry India

by - 14th August 2015

AS 82-year-old Sikh activist Surat Singh Khalsa resumes his hunger strike to demand the release of Sikh political prisoners across India, a White House petition has been launched by the Organisation for Minorities in India to draw global attention to the issue.

Khalsa, a US citizen, has been on indefinite hunger strike in Punjab since 16 January 2015, and has been arrested and force-fed three times. He was recently discharged from hospital on 6 August, but resumed his fast.

These recent developments have coincided with other political activities in the region that has the Indian government worried about the revival of Sikh nationalism.

On 6 August, the Punjab police also arrested a number of Sikh hardliners who were planning to organise a protest to extend their support to Khalsa.

And when a group of militants allegedly from Pakistan attacked a small town, in the Gurdaspur district in Indian state of Punjab on 27 July, the political and media circles in India were abuzz with fear of the revival of Sikh militancy.

Seven people, including the Superintendent of Police and three other policemen were killed in the attacks. The fire-fight broke out after three heavily-armed militants slipped across the Indian border from Pakistan.

Though the involvement of Sikh militants in the attack was later debunked, the Indian administration and the intelligence community have been increasingly concerned about the revival of Sikh nationalism and Pakistan’s role in it.

Links to Pakistan

India’s government has repeatedly claimed that Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), and the armed outfits it allegedly sponsors, are trying to revive Sikh militancy and fuel the demand for an independent so-called 'Khalistan' – a theocratic Sikh state.

The recent attack brought back memories of the civil strife in Punjab, between the Indian state and numerous Sikh groups, including separatist organisation, during much of the 1980s and 1990s.

According to the South Asia Terrorism Portal, 11,786 civilians and 1,754 security personnel were killed between 1981 and July 2015 in ‘terrorist’ attacks in the state. Of this 2,591 civilians died in 1991 alone.

Indian sources claim that Pakistan was engaged in a proxy war to destabilise India, and it increasingly used the domestic turmoil in the Indian state of Punjab to do so.

Writing for the Indian web-portal Firstpost, Rajeev Sharma claims that ‘The revival of militancy in Punjab would be a huge strategic victory for Pakistan which India can ill afford to concede.’

In 2009, India’s Central Intelligence claimed that there was a meeting between the members of Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM) and the Babbar Khalsa International (BKI) in Pakistan, under the aegis of ISI, to plan an attack within India during the general elections.

In 2013, the then home minister of India Sushil Kumar Shinde accused Pakistan of training Sikh hardliners on its soil, an accusation that Pakistan claimed was uncalled for and counter-productive.

On 12 July, a number of media organisations in Pakistan reported that #LiberateKhalistan was trending in Pakistan. And even as Indian administration blamed Pakistan after the recent attacks, social media in Pakistan too was buzzing with comments and hashtags suggesting that India itself perpetrated the attacks.

#ModiAttacksGurdaspur was one of the most trending hashtags among Pakistan’s twitterati.

After a deadly wave of ethno-nationalist conflict in the 1980s and 1990s, actual violence in Punjab has decreased significantly even though the state of governance in the region has been dismally poor in the period of peace.

Grievance

This fear of revival, however, goes beyond actual incidences of violence. For example, the Indian intelligence has also warned of the growing number of movies that glamorise the Khalistan movement, while reinforcing the atrocities during the Hindu-Sikh riots in the 1980s. A number of these movies have been withdrawn from public distribution.

Poor governance, growing crime rates and a destructive drug culture among the Punjab's youth are increasingly seen as challenges and indicative of social breakdown that neither the central nor the state governments can address.

Speaking against the state government's response to the murder of Police Assistant Sub-Inspector (ASI) Ravinder Pal Singh back in 2012, Dr Gurmit Singh Aulakh, President of the Council of Khalistan, a US-based organisation fighting for an independent Sikh homeland said, ‘We need a free Khalistan.’

‘Only a free and independent Khalistan will allow Sikhs to end the moral degeneration of our people,’ he added.

The Indian state is especially concerned about Sikh organisations outside India that lend support to the demand of an 'independent Khalistan' and are increasingly involved in localised politics.

Some experts argue that especially since the mid-1990s, the so-called 'Khalistan movement' finds more resonance among the Sikh diaspora in Britain, US and Canada than in Punjab itself.

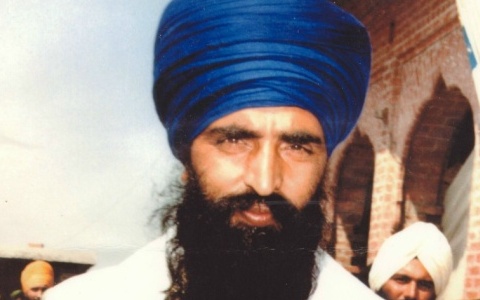

Simrat Dhillon, in an authoritative research paper for New Delhi’s Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies, The Sikh Diaspora and the Quest for Khalistan, argued in 2007 that the Sikh diaspora mobilised itself after the Indian army attacked the holiest of Sikh shines, the Golden Temple in June 1984 and killed among others the charismatic preacher and militant leader Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale.

The wave of violence against the Sikh community that followed the assassination of the Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in October 1984 also fuelled this mobilisation, she argued.

The continued lack of justice for the victims of the anti-Sikh riots in Delhi is another issue that the Sikh diaspora has successfully internationalised.

Ahead of the 2015 UK elections, for example, the Sikh Federation, a registered political party in the UK, launched the Sikh Manifesto, in which it demanded, among other things, a UN-led investigation of what it called the ‘1984 Sikh genocide’.

It also demanded an independent investigation into the role played by the UK government, and for the UK to accept the right of Sikhs to exercise self-determination in India.

The manifesto received support from a wide array of political leaders including Ed Miliband, Nicola Sturgeon, Nick Clegg and even Nigel Farage.

In 2013, the Indian government warned a number of US congressmen and the Obama administration against being involved in the Sikh Congressional Caucus, established with the objective of fighting hate crimes against the community, especially after the Oak Creek shooting in Wisconsin in 2012 in which six Sikhs died, saying it was led by pro-Khalistani supporters.

More than land

Even in the 1980s, the Khalistan movement has been more than just a demand for a separate homeland for the Sikhs.

For advocates of Khalistan, their demand was fuelled by an economic rationale that was against ‘Hindu colonialism’, ‘Hindu capitalism’ and the ideology of karma, espoused by Brahmins and Banias which suppressed the poor and made people timid, argues Birinder Pal Singh, professor at the Punjabi University in Patiala.

Cynthia Keppley Mahmood, Senior Fellow in Peace Studies, Department of Anthropology, University of Notre Dame writes that the origin of the Khalistan movement goes beyond the 1980s to at least the 1960s during the Punjabi Suba movement, a political movement to create a separate Punjabi-speaking state.

However, a number of scholars including Harnik Deol and Gurpal Singh argue that the root of Sikh nationalism pre-dates colonial rule as ethnic identity is based on religious traditions and the territorialisation of Sikh social-political identity.

It was the tenth and the last Guru of the Sikhs, Guru Gobind Singh, who re-established the Sikhs as a military group called the Khalsa in 1699 to counter the persecution of the community.

Groups advocating for an independent Khalistan tap into this religious symbolism to draw legitimacy and relevance especially in times of political and social uncertainty.

Political cycle

The stirring up of the Khalistan issue has unsurprisingly coincided with the electoral cycle.

Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD), the party heading the Punjab state government, has been courting Sikh hardliners for votes by promising to release a number of Khalistan militants currently in custody.

It is a plan the Indian Supreme Court does not support.

Even the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), SAD’s coalition partner, does not support these demands. In January 2015, it disagreed with Badal’s attempt to seek premature release of 13 Khalistan militants.

But Khalsa’s lime-water fast is putting Chief Minister Prakash Singh Badal under acute pressure, as public support, including that of Giani Gurbachan Singh, the Jathedar of Akal Takht, one of the highest Sikh leaders, grows.