ANALYSIS: Malaysia's progressive Muslims want a secular future

by - 1st March 2017

Malaysia is a country in ferment.

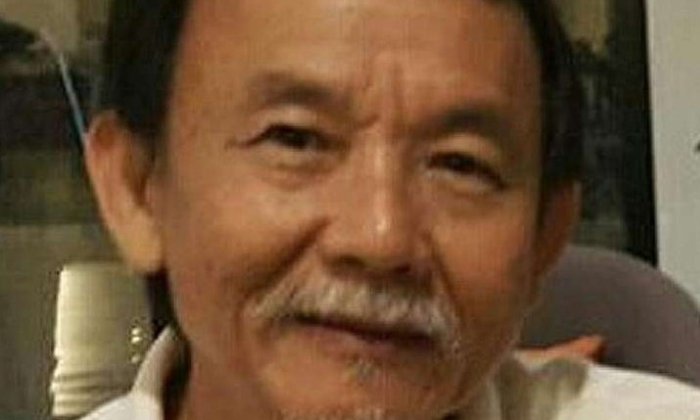

The abduction of protestant Pastor Raymond Koh missing since 13 February after being snatched from a street in Petaling Jaya near the capital Kuala Lumpur, comes against a background of pressure against non-Muslims.

The growing demand for Islamic criminal punishment codes, known as hadd or hudud (plural Arabic for 'prohibitions'), which set Pakistan on the road to ruin, is worrying .

Hudud crimes warrant severe corporal punishments, including stoning for adultery, and death for apostasy. Though limited by rules of evidence, their implementation on any statute book creates consternation, and at worst, as in Pakistan, mob rule.

Yet demand for and implementation of such penalties are creeping in from conservative fringe states in Malaysia.

Emerging

Malaysia is described by the CIA as ‘a middle-income country [that] has transformed itself since the 1970s from a producer of raw materials into an emerging multi-sector economy’, so the hadd development has huge ramifications, and a crucial subtext in potentially volatile identity politics

Since independence, first as Malaya in 1957 then as the enlarged Malaysia in 1963, the country has witnessed a tussle between two parties vying for the support of the majority Malay race - who are all Muslim.

The United Malays National Organisation, or UMNO, has been the driver in the ruling coalition since independence, originally representing a more modernizing approach to Islam. Its principal rival for Malay support is the conservative Islamic party, known by its Malay acronym, ‘PAS’.

Muslims constitute sixty per cent of the population, with the remaining forty per cent divided among Buddhists, Hindus, Christians, various Chinese religions and other minor religious groupings.

Malaysia has a lot going for it. It represents the meeting place of three of the world’s greatest civilizations: Malay, Chinese and Indian, all making a significant contribution to the nation.

As such, Malaysia could be a dynamic laboratory for Islamic religious pluralism. Yet for forty years, the drift has been towards increasingly narrow religious exclusivism.

Identity

For the first decade of its existence Malaysia flourished as a multicultural, multifaith state.

Then bitter race riots in 1969 left a legacy of fear among the majority Malay race that their predominance was threatened.

Under the leadership of Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad during the 1980s and 1990s, the UMNO-led coalition government sought to entrench Malay predominance by strengthening Islam in the fabric of the state.

The Mahathir government introduced a raft of Islamic legislation and established a diverse set of Islamic institutions: Islamic banks, an Islamic Economic Foundation, an Islamic foundation for social welfare, an Islamic Centre within the Prime Minister’s department, Islamic universities, and many more institutions.

This resulted in the creation of a powerful Islamic bureaucracy at both federal and state levels. The UMNO-led government spoke the language of ‘Islamic values’; their rivals in the Islamic Party PAS in response out-bid them and called for Islamic law. The country witnessed a spiral of Islamization as the two political groups slugged it out to win the hearts and minds of the majority Malays.

The impact on religious minorities

The forty per cent non-Malay religious minority meanwhile felt marginalized as institutions assumed an increasingly Islamic hue. One key area affected was education, as explained by Tan Kong Beng, Executive Secretary of the Christian Federation of Malaysia, who told Lapido: ‘Creeping Islamization in Malaysia’s schools has been going on for over twenty years.’

This is reflected in many ways, including the favouring of Muslims in teacher recruitment and in the curriculum. The study of Islam is enhanced in government schools and the study of other faiths is excluded, replaced by ‘ethics’.

Even more debilitating for inter-religious harmony is the subtle humiliation of non-Muslims in their dealings with government that has sometimes accompanied the Islamization process.

Tan Kong Beng explains: ‘We have to be over-courteous in formal meetings. The form of courtesy is: “Pardon my ignorance, I would like to ask a question.”’

Dr Hermen Shastri, General Secretary of the Council of Churches of Malaysia, concurs. Inter-religious meetings with Government are constrained, he says. ‘There is this constant permeation of a culture of fear. Somehow you cannot be open about taking a different stand.'

The hudud debate

In a context of pervasive interfaith dysfunction, the introduction by the leader of PAS of a private member’s bill calling on the Malaysian Federal Parliament for hudud criminal codes will hardly help.

In a context of pervasive interfaith dysfunction, the introduction by the leader of PAS of a private member’s bill calling on the Malaysian Federal Parliament for hudud criminal codes will hardly help.

Sitting just off stage on this hudud issue is the powerful Islamic bureaucracy, created by the UMNO-led government.

Eugene Yapp, Executive Director of the Kairos Dialogue Network, an NGO dedicated to dialogue on issues affecting Christian-Muslim relations, claims that the religious bureaucracy aims to widen the powers of the shariah courts to facilitate the implementation of hudud laws.

‘It is part of its plan to review the entire shariah judicial system, which includes upgrading the levels of the shariah court and the harmonization of shariah and civil laws, as part of the Islamization agenda’, he said.

This is not good news for Malaysia’s religious minority population who find small comfort in the assurances by the authorities that it will only apply to Muslims.

Cases of non-Muslims having to comply with Islamic regulations already abound in today’s Malaysia. Several examples will suffice.

Kissing

Two Chinese non-Muslim young people were charged in the City Hall magistrate’s court with hugging and kissing in a park, just last year.

And a middle-aged Chinese woman was refused service in a Department of Transport office until she covered her bare lower legs with a sarong, an ankle-length item of Malay apparel.

Food items popular among non-Muslim (and many Muslim) Malaysians which carry names considered offensive to Muslims - such as ‘ginger beer’ and ‘hot dog’ - have had to change their names in order to receive halal certification.

Police raided Chinese shops in several Malay cities recently for selling paint brushes that were suspected of containing pig bristles.

And as an example of bottom-up pressure, a group of Muslims demanded the removal of the cross from a church in a public square in Selangor.

Where to from here?

There is a mood of pessimism among Malaysia’s Christians. Dr Ng Kam Weng, Christian Director of the Kairos Research Centre, says the Islamic bureaucracy talks about implementing shariah ‘in phases’.

‘Whatever they say, we know that their ultimate goal is hudud. Even without present attempts to enhance shariah courts, they are already infringing our rights. What more when shariah courts are enhanced further and other steps embolden them?

‘The record shows that they have no respect for my constitutional rights even within the present constitutional system. So we have no reason to believe that they would do any better [with enhanced shariah courts] and probably would do worse.’

But there are some positive signs on the horizon. For one, Malaysia’s two eastern states on the island of Borneo, Sarawak and Sabah, have substantial Christian populations and have come out strongly against the proposed introduction of hudud codes.

Another positive sign is the support the religious minorities are receiving in some issues from progressive Muslim groups.

Hermen Shastri adds: ‘The [Muslim NGOs] we find most helpful are those who have made up their mind that Malaysia is secular and there is nothing un-Islamic about that.

‘Malaysia was never meant to be an Islamic state. This has only come to excess because of having one government rule for so long.’

Prof Peter G Riddell serves as Professorial Research Associate in the Department of History at SOAS, University of London and as Vice Principal (Academic) at the Melbourne School of Theology (an affiliated college of the Australian College of Theology). He previously taught at the Australian National University, the Institut Pertanian Bogor (Indonesia), and the London School of Theology. He has published widely on the study of Southeast Asia, Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations.

Prof Peter G Riddell serves as Professorial Research Associate in the Department of History at SOAS, University of London and as Vice Principal (Academic) at the Melbourne School of Theology (an affiliated college of the Australian College of Theology). He previously taught at the Australian National University, the Institut Pertanian Bogor (Indonesia), and the London School of Theology. He has published widely on the study of Southeast Asia, Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations.