BRIEFING: The roots of conflict in Yemen – no easy answers

by - 22nd April 2015

THE prophet Muhammad is recorded as saying: ‘When disaster threatens, seek refuge in Yemen.’

He spoke those words after he and his small band of followers had been driven out of Mecca, and before it was clear that their emigration – the Hijra – to Medina would prove the success that turned the tide in favor of the new religion. Not surprisingly, then, religion means much to the Yemeni people and Yemen much to pious Muslims.

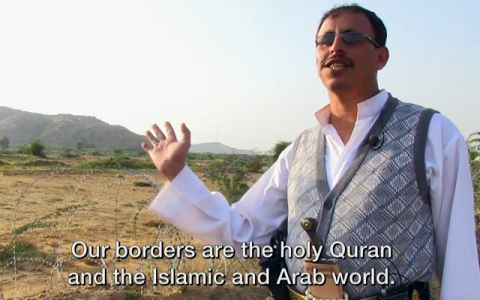

Indeed, less than a minute into the April 2015 PBS Frontline special on Yemen, reporter Safa Al Ahmad is told by a Houthi informant ‘Our borders are the Holy Quran and the Islamic and Arab world’.

In an article titled The Middle East’s Franz Ferdinand Moment: Why the Islamic State's claimed attack in Yemen could spark an Arab World War, JM Berger of Brookings gives us context:

‘The crisis in Yemen is one of the more complicated stories to emerge from a complicated region. It involves a cyclone of explosive elements: religious extremism, proxy war, sectarian tension, tribal rivalries, terrorist rivalries and US counterterrorism policies. There is little consensus on which element matters most, although each has its fierce partisans.’

Berger offers the bombing of two Sanaa mosques on March 20 as his candidate for the spark that ignited the current situation in Yemen – just as the bombing of the Shiite al-Askari Mosque in Samarra was a turning point leading to all-out sectarian civil war in Iraq.

Scriptures

Westerners don’t generally think about scriptures when they’re discussing borders, although the concept of ‘Greater Israel’ references Biblical texts such as Genesis 15.18: ‘Unto thy seed have I given this land, from the river of Egypt unto the great river, the river Euphrates.’

To the mostly secular western minds of our decision makers, not to mention the traditionally and appropriately sceptical minds of our journalists, scriptures are peripheral to geopolitics: what counts adds up to what can be counted – personal and materiel, times and distances, the stuff of logistics. All these things are important, but they don’t address the key issue of motivation.

Seen from an Islamic perspective, however, the spiritual world – invisible to the secular mind – is where the real action takes place.

Thus the Qur’an (3.125) describes the seminal battle of Badr in these terms: ‘Yea; if you are patient and godfearing, and the foe come against you instantly, your Lord will reinforce you with five thousand swooping angels.’

In Yemen, matters of religion are among the key factors we urgently need to understand. Other factors of importance that we are liable to miss will include water shortages – Yemen is the seventh most ‘water-stressed’ country in the world, see Analysis: Water shortages and violence in the Middle East – but it is religion that concerns us here, and the religious situation in Yemen is complex to say the least.

Differences

The two main religious groupings in Yemen, the Shia Zaidi and Sunni Shafi, have traditionally gotten along well together. Given that the Zaidis are nominally Shia, it is easy to forget that their Shiism is distinct from that of Iran, that they recognise only five Imams rather than the twelve recognized by the majority of Shia, and that their theology is open to diverse views, many of them closer to those of their Sunni neighbors than to those of Khomeini or Khamenei’s Iran:

‘It is a sect that is open to development and improvement, and even encompasses [the ideas of] Salafist clerics, such as Sheikh Mohamed Ibn Abd-al-Wahab and Muhammad ash-Shawkani. The Zaidi sect also encompassed religious figures who took the Zaidi doctrine to the extreme, such as Imam Abdullah Bin Hamza who massacred a group of his subjects known as the ‘al-Mutrafeya’ because they argued that it was not mandatory that a ruling imam be a descendent of Al-Hassan or Al-Hussein. The Zaidi sect also includes independent jurists and freethinkers, like Mohamed Bin Ibrahim Bin al-Wazir, who died in 1437, and who advocated freeing oneself from all sectarian and doctrinal attachments and solely embracing the teachings of the Holy Quran and Sunnah. And so the Zaidi sect included freethinkers, as well as fanatics.’

So wrote Mshari al-Zaydi in Asharq Alawsat in 2009.

Col Pat Lang, who initiated the study of Arabic at West Point and has served extensively in Yemen, comments: ‘The zaidiya follows a system of religious law (sharia) that more closely resembles that of the Hanafi Sunni ‘school’ of law than that of the Shia of Iran or Iraq. The Zaidi scholars profess no allegiance to the 12er Shia scholarship of the Iranian teachers. In theology the Zaidis follow the methodology in analysis of the mu'tazila , the ‘rationalist’ school of theology exterminated in the rest of Islam (including Iran) 1200 years ago.’

And Gregory Johnson, perhaps our best contemporary writer on Yemen, even refers to the Zaidi in his book,The Last Refuge: Yemen, al-Qaeda and America's War in Arabia as both Sunni and Shia: ‘Adopting the flexibility of marginalized groups, Zaidis charted a sort of middle course between Sunni and Shi'a. They were “fivers,” the unofficial fifth school of Sunni Islam and followers of the fifth Imam in Shi'a Islam. In Yemen, they were almost indistinguishable from their lowland Sunni neighbors ... The two groups intermarried and prayed in each other's mosques.’

Complexity

The religious picture, then, is a complex one, further complicated by al-Zaidi’s injunction in the title of his piece quoted above, Don't Confuse the Huthis with the Zaidis. Specifically, Zaidi suggests, ‘The Huthis are an extremist version of the Zaidi sect, and some researchers believe they are an extension of a well-known Zaidi offshoot, the al-Jarodiah sect.’

The Houthis, meanwhile, have indeed been receiving arms and support from Iran, and in the wider Middle Eastern context can be viewed as potential members of the ‘Shi’a crescent’ King Abdullah of Jordan warned about in 2004.

Thus ex-CIA analyst Graham Fuller recently wrote: ‘From Riyadh's perspective, Tehran has supposedly pocketed Iraq, is successfully keeping Assad in power in Syria, threatens Bahrain, stirs oppressed and restive Shia within the Saudi Kingdom, and now bids to control Yemen, thereby “encircling the Peninsula".’

Despite the flexibility of Zaidi beliefs and its general proximity to Sunni and particularly Hanafi jurisprudence, there are also suggestions that the Houthis may now be aligned with Iran in much the same way that Nazrallah and Hizbollah are – both in terms of weaponry and support, and in ideology.

As far back as 2009, Israeli-based MESI analysis was reporting an Iranian source as saying ‘Yemeni Shi'ite Cleric and Houthi Disciple 'Issam Al-'Imad: Our Leader Houthi is Close to Khamenei; We Are Influenced Religiously and Ideologically By Iran’.

Timothy Furnish, whose 2005 book Holiest Wars is the go-to source on Mahdist movements, makes further points in a Wikistrat briefing: ‘One might well argue .. that the Houthi's Zaydi leadership is using Tehran more than the other way around. For much of the last 1200 years, Zaydis have ruled over much of Yemen and they do have legitimate grievances against both the recent Sunni leadership in Sana’a and, of course, against Sunni jihadists like Al Qaeda and (allegedly) ISIS there. Saudi Arabia’s reflexive theological and political fear of Shiism in the peninsula is understandable as well. Besides Yemen, there are large minority pockets of Twelvers in eastern Saudi Arabia and of Seveners in Najran.’

And here’s another point Furnish makes that is seldom mentioned: ‘Also, Mahdism has been a real fear since 1979, when Juhayman al-Utaybi declared his brother-in-law, Muhammad al-Qahtani, the Mahdi and their forces occupied the Great Mosque — a fear that has grown in recent years as Saudi Arabia has suffered a rash of “lone wolf” Mahdis across the kingdom.’

According to David Cook (Studies in Muslim Apocalyptic, Princeton: Darwin, 2002), there are even some very obscure references to the possibility that the Mahdi's birthplace will be in Yemen.

All in all, there’s more religious complexity here, in other words, than a non-specialist journalist or general reader can reasonably be expected to follow, but several points remain clear:

- not all Zaidis are Houthis

- the Zaidi are in many ways closer to Sunnis than to Iranian ‘Twelver’ Shia

- the Houthis may be moving ideologically towards, Iran

- the Saudis thus view them as part of a potential ‘Shia crescent’ – and thus

- a far more complex situation plays out within the sectarian rivalry of KSA vs Iran

Sectarian

And that large scale ‘sectarian’ analysis itself still needs further qualification. As Thanassis Cambanis observed in a recent Foreign Policy piece: ‘We are witnessing a struggle for regional dominance between two loose and shifting coalitions — one roughly grouped around Saudi Arabia and one around Iran. Despite the sectarian hue of the coalitions, Sunni-Shiite enmity is not the best explanation for today’s regional war. This is a naked struggle for power: Neither of these coalitions has fixed membership or a monolithic ideology, and neither has any commitment whatsoever to the bedrock issues that would promote good governance in the region.’

It should be apparent that comments such as the recent Reuters report that the Houthis ‘share a Shi'ite ideology’ with Iran are half-truths at best.

Our decision-makers deserve more than a quick-and-dirty sound-bite analysis – if they are to make wise choices, they need to request – and hearken to -- genuine expertise of the sort people like Farea Al-Muslimi, Michelle Shephard and Gregory Johnsen can offer.