None the wiser ten years on: The Telegraph’s failure to get 9/11

by - 11th May 2011

The tenth anniversary of the Al Qa’eda attacks of 11 September 2001 against the U.S. approaches. Osama Bin Laden is dead. But moderate Muslims are reminded daily that Western political and media leaders have learned little, in this decade, about Islam in general, and radical Islamist ideology in particular.

The tenth anniversary of the Al Qa’eda attacks of 11 September 2001 against the U.S. approaches. Osama Bin Laden is dead. But moderate Muslims are reminded daily that Western political and media leaders have learned little, in this decade, about Islam in general, and radical Islamist ideology in particular.

This failure of comprehension is exemplified by a column in The Daily Telegraph [London] of 26 April 2011. Written by Ed West, it is titled ‘Why does Britain have an Islamist problem while America doesn’t? Answer: the welfare state.’ In it, Mr West states several assumptions about radical Islam in Britain and America that do not bear up under scrutiny by moderate Muslims.

He writes, ‘London was the global headquarters of Islamic terrorism in the years before and after 9/11…London became the world terrorist hub partly because the country had a long tradition of shielding dissenters of all stripes...and because of Britain’s historic links with many Arab countries. But there was another reason, and this is central to the reason why Europe has an Islamist problem and the United States doesn’t – the welfare state. Welfare is intimately linked to the failure of western European countries to integrate their Muslim populations, and explains why Britain has such a problem with Islamism.’

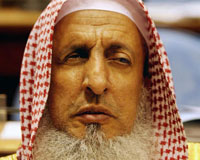

These claims are contrary to obvious realities. First, the charge that London was ever ‘the global headquarters of Islamic terrorism’ rests on no evidence. As moderate Muslims know, and has been documented repeatedly in recent years, the ‘headquarters’ of Islamist terrorism are located in Saudi Arabia, the home of Wahhabism, the most violent and exclusionary form of Muslim fundamentalism ever to claim the mantle of Sunnism. Subordinate centres are found in Yemen, where the Saudis ‘exported’ the Al Qa’eda cadres from their territory, and in Pakistan and Afghanistan, where the Wahhabi-like Deobandi sect and the ‘bi-national’ Taliban began their ignominious careers. The Saudi ‘headquarters’ does not consist of an institution or even of publicly-known individuals. Since 2005, Saudi King Abdullah has worked to remove Al Qa’eda activities from Saudi agencies in which it originated. The Saudi ‘headquarters’ consists of rich individuals, some of them inside the royal family and still within state and religious bodies, who continue financing terrorism coordinated from Yemen and South Asia. They are provided with fake religious legitimacy by clerics like Abdur-Rahman Al-Sudais, the Friday preacher at the grand mosque in Mecca, who recently visited India to celebrate the unity of Wahhabism and Deobandism.

These claims are contrary to obvious realities. First, the charge that London was ever ‘the global headquarters of Islamic terrorism’ rests on no evidence. As moderate Muslims know, and has been documented repeatedly in recent years, the ‘headquarters’ of Islamist terrorism are located in Saudi Arabia, the home of Wahhabism, the most violent and exclusionary form of Muslim fundamentalism ever to claim the mantle of Sunnism. Subordinate centres are found in Yemen, where the Saudis ‘exported’ the Al Qa’eda cadres from their territory, and in Pakistan and Afghanistan, where the Wahhabi-like Deobandi sect and the ‘bi-national’ Taliban began their ignominious careers. The Saudi ‘headquarters’ does not consist of an institution or even of publicly-known individuals. Since 2005, Saudi King Abdullah has worked to remove Al Qa’eda activities from Saudi agencies in which it originated. The Saudi ‘headquarters’ consists of rich individuals, some of them inside the royal family and still within state and religious bodies, who continue financing terrorism coordinated from Yemen and South Asia. They are provided with fake religious legitimacy by clerics like Abdur-Rahman Al-Sudais, the Friday preacher at the grand mosque in Mecca, who recently visited India to celebrate the unity of Wahhabism and Deobandism.

Wahhabism and Deobandism appeared at different historical places – the first in the wilderness of central Arabia (Najd) in the eighteenth century, the second in British India in the nineteenth. At the beginning, they were both fundamentalist, but differences existed between them. Wahhabism wiped out traditional Islamic jurisprudence and prohibited Sufi observances. Pakistani Deobandism held to Hanafism, the most rational school of Islamic jurisprudence, which was established from the Balkans to South Asia. Coming from India, with its long-established Sufi traditions, the Deobandis were not, at first, homicidally hostile to Sufis – they have been taught this, or it has been imposed on them, by their Saudi Wahhabi financiers and Pakistani supervisors.

Wahhabism and Deobandism appeared at different historical places – the first in the wilderness of central Arabia (Najd) in the eighteenth century, the second in British India in the nineteenth. At the beginning, they were both fundamentalist, but differences existed between them. Wahhabism wiped out traditional Islamic jurisprudence and prohibited Sufi observances. Pakistani Deobandism held to Hanafism, the most rational school of Islamic jurisprudence, which was established from the Balkans to South Asia. Coming from India, with its long-established Sufi traditions, the Deobandis were not, at first, homicidally hostile to Sufis – they have been taught this, or it has been imposed on them, by their Saudi Wahhabi financiers and Pakistani supervisors.

Saudi money and Pakistani Islamist coordination turned the Pakistani Deobandis into the Taliban. Pakistani Deobandism became ‘Wahhabised’ when the Saudis and Pakistanis needed a fundamentalist group to govern Afghanistan. This came after the Russians had departed in 1989, Afghan Communism had fallen in 1992, and the country had descended into factional chaos. In 1995, Deobandi students from medresas in Pakistan were sent into Afghanistan to establish the Taliban regime (‘talib’ is Arabic for student). Money trumped doctrinal or cultural differences between the two forms of radicalism.

Mr West cites the British cases of Abu Qatada, Abu Hamza, Omar Bakri Mohammad, Anjem Choudary, and the participants in the 21 July 2005 bombings, all of whom were the subjects of widespread UK media reportage. Yet none of these figures gained a large following. Britain has suffered several important terrorist incidents and attempts, comprising the 7 July 2005 London tube attacks, the 2006 trans-Atlantic airline plot, and the 2007 London car bomb and Glasgow airport conspiracies. The UK remains the epicentre of radical Islam in western Europe. But Mr West’s comparisons with the US amount to little more than polemics.

Since the 2007 attacks, terrorism has declined in Britain, while several later and especially disturbing Islamist atrocities have taken place in the US. These include the 2009 Fort Hood, Texas, shooting assault by an army doctor, Nidal Malik Hasan, in which 13 people were killed and 29 wounded. In that year alone, 10 out of nearly 30 Islamist terror schemes discovered since 2001 in the US were shut down. The horrific Fort Hood mass murder was followed by the Christmas 2009 attempt by Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab to bomb an airliner over Detroit, Michigan. In 2010 came, among other such episodes, the Times Square bombing attempt in New York, which fortunately took no lives, and the arrest in the Washington, DC area of Farooque Ahmed, charged with planning explosive attacks on the local metropolitan transit system. Inspiration and guidance for most of these acts came from Yemen. Anwar Al-Awlaki, now the main Al Qa’eda theoretician, operates from Yemen but is a US citizen by birth.

The UK and US are indeed the main Western theatres of the anti-terror struggle among Muslims and between governments and their violent Islamist enemies. But the reasons for this are unconnected to welfare economics. In my observation across the Muslim communities of England, more moderate Muslims receive benefits than do radicals, because moderates are concentrated in economically depressed areas, while radicals are mainly drawn from among urbanised professionals. The prevalence of radicalism in British and American Islam has to do with the importation of a well-financed extremist ideology, mainly, as previously indicated, from Saudi Arabia and South Asia.

Mr West writes correctly about ‘the failure of western European countries to integrate their Muslim populations.’ But other European countries with equally or more generous welfare schemes than the UK, such as France and Germany, have Muslim communities larger than that in Britain, and they also have yet to be integrated into the broader society. According to the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, the UK in 2010 had around 2.8 million Muslim residents, or less than five percent of the total population, while France had almost five million or 7.5 percent, and Germany had four million, or five percent. Still, France and Germany have been spared significant terrorist attacks since 2001.

Moderate Muslims do not believe that Islamist extremism is a product of Western governmental welfare policy, or even of the social marginalization, which, to emphasize, Mr West avers is absent in the US, where ‘well over two thirds of American Muslims said they believed they can make it in America with hard work.’

Paradoxically, most American Muslims may share such beliefs about their adopted land, but as I and others have observed, American Islam is dominated by a radical ideological coterie also subsidised from Saudi Arabia and South Asia. To cite one notorious example, the Islamic Circle of North America (ICNA), which controls important American mosques, is a front for the radical Jamaat-e-Islami (JeI) in Pakistan. There is no restriction on JeI activities in the UK. Nor is it apparently recognised by British authorities that Deobandi preachers, representing no more than a quarter of British Muslims, have carried out an aggressive campaign of mosque construction in the UK, and have decisive influence in the Muslim Council of Britain (MCB).

South Asians, mainly from Pakistan and Bangladesh, and their descendants, form the majority of UK Muslims and a plurality of immigrant Muslims and their offspring in the US, although the latter figure is ambiguous because the US does not collect census figures on religion. Throughout these communities, the South Asian Barelvi mosques favouring moderation, loyalty to the national, non-Muslim laws and government, and Sufi spirituality have faced serious obstacles in uniting against the radicals. The UK authorities and media have not alleviated this situation. Rather, by ignoring the real issues in British Islam, which may be traced back to Saudi and South Asian jihadism, they have aggravated them. Saudi and South Asian Islamist extremism has become a discouraged topic, much more controversial than criticism of the welfare state, because of ‘political correctness’ in the British elite. Mr West cites ‘Britain’s historic links with many Arab countries’ as a factor in jihadism in the UK. Those links are important, especially regarding Saudi Arabia, but similar connections with South Asia are no less important.

South Asians, mainly from Pakistan and Bangladesh, and their descendants, form the majority of UK Muslims and a plurality of immigrant Muslims and their offspring in the US, although the latter figure is ambiguous because the US does not collect census figures on religion. Throughout these communities, the South Asian Barelvi mosques favouring moderation, loyalty to the national, non-Muslim laws and government, and Sufi spirituality have faced serious obstacles in uniting against the radicals. The UK authorities and media have not alleviated this situation. Rather, by ignoring the real issues in British Islam, which may be traced back to Saudi and South Asian jihadism, they have aggravated them. Saudi and South Asian Islamist extremism has become a discouraged topic, much more controversial than criticism of the welfare state, because of ‘political correctness’ in the British elite. Mr West cites ‘Britain’s historic links with many Arab countries’ as a factor in jihadism in the UK. Those links are important, especially regarding Saudi Arabia, but similar connections with South Asia are no less important.

Ten years after 11 September 2001 and almost six years after the 7 July 2005 bombings in London, commentators like Ed West continue seeking to assign blame where it does not belong. The welfare state is an easy target. The role of Saudi Arabia and Pakistan in British policy and of Saudi money and South Asian activists in the radicalisation of British Islam is a much more difficult issue.

- Log in to post comments