Freedom in Cuba remains a dream - writes former World correspondent

by - 30th November 2016

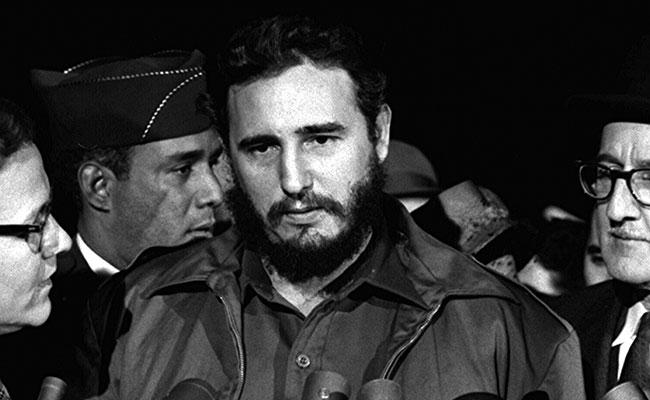

CASTRO was educated by Jesuits, but he closed churches, nationalized properties owned by religious organizations and forced the faithful underground.

It’s no better today.

I first travelled to Havana in 1991 at the peak of the so-called ‘special period’, a time of severe economic restrictions that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union, Cuba's main ally.

It was a particularly hard time for Cubans. There were shortages of food, petrol and other basic goods. Men and women could be seen queuing for hours for the few buses available, already packed with people on their way to work.

Walking through the streets of Old Havana people would ask tourists and foreign residents for basic items such as soap, shampoo, toothpaste, toilet paper, you name it.

Others took a much greater risk by offering to change money in the black market. This had to be done discreetly though as it was an illegal practice. Any Cuban citizen caught with dollars in their hands could be sent straight to jail.

Cubans who voiced their discontent with Castro's regime had to do so in a whisper. To this day dissent is considered a crime. Hundreds of political dissidents are still behind bars in Cuban prisons.

Timid reforms for ordinary Cubans

Under the weight of the economic crisis, Castro had to be pragmatic, and in the mid-nineties his government implemented a series of timid reforms including allowing Cubans to work independently and set up their own ‘businesses’, although this soon proved to be something of a misnomer.

The list of more than a hundred so called ‘professions’ included things like button liner, spark plug cleaner, coffee street peddler, umbrella repairman, broom seller, custard maker and owner of a paladar, a small restaurant in your own home with only 12 seats and a fixed menu that had to be approved by the authorities.

Perhaps the most common trade still today is taxi driver. Before I had my own means of transport – a Scooter - to go about Havana doing my reporting work, I often hired the services of a Cuban friend of mine, an electronic engineer who had been unemployed for a few years.

He would drive me around in a white Russian Lada he used as a taxi. It was an old car, its engine always took several attempts to start, so once at our destination and while he waited for me, he wouldn't risk turning off the engine in case it didn't start again. He made more money this way than in any other job he could possibly have.

It didn't take long for me to spot the main personality traits of Cubans, perhaps traits they inherited from Castro himself, who was for many an ever-present father figure: Cubans like Castro are ingenious, cunning, vivacious, seductive and talkative.

A talker, not much of a listener.

Over the years Cubans dedicated thousands of hours to listening to Castro's televised speeches. Families sat in front of the television set to see their Commander in Chief and get whatever news he would announce, if any at all. More often than not it was simply a long and tedious monologue and an effective brainwashing exercise.

In his persistent rhetoric, Castro always pointed an accusatory finger at the US for imposing a trade embargo on Cuba – he called it a blockade - which he blamed for all the country's ills and the struggles people have to endure to this day. This became a sort of mantra he recited in every speech. His exact words would often be repeated afterwards by ordinary Cubans

The late Colombian writer Gabriel García Marquez, who forged a very close friendship with Castro, once said that Fidel's ‘devotion to words’ was ‘almost magical’ and that he considered three hours a good average for an ordinary conversation.

As part of the foreign press corps I was once invited to a meeting with Fidel Castro at the government headquarters in the Revolution's Palace. The meeting started at 7:00pm, we asked questions and he gave his usual long answers. One of his responses to a particular question about an alleged plot to assassinate Hugo Chavez, Venezuela's late President and one of his closest allies in the region, took almost 45 minutes.

By 3.30am we were all struggling to keep our eyes open and thought surely the meeting would soon be over. But instead of sending us off, he summoned his chef and asked him to bring something to eat. A flurry of activity soon followed while he kept talking. Tables were set impeccably: white linen tablecloths, fine silver cutlery and wine glasses. The food was brought a few minutes later: yoghurt and a grapefruit for him; canapés, bowls of fruits, French cheeses and red wine for us. I was back home at 6.00am.

Revolution in faith

When the Pope arrived in Havana in January 1998, he encountered a Catholic Church determined to keep its dim flame alive. One of the biggest challenges the church faced back then and still today was building a strong local-based leadership, something that has never been achieved in Cuba.

Shortly after his coming to power, Castro closed churches, nationalized properties owned by religious organizations and forced the faithful underground. The sweep was so broad in the 1960s that Castro even closed down the Jesuit high school he and his brother Raúl attended, forcing the priests to pack up and go. Cuba was left with just a handful of priests to do pastoral work in an increasingly hostile environment.

It was not until 1992 that the Cuban government began to ease restrictions on open displays of religion. It allowed churches to reopen and ended a long-standing ban on the work of charities and other social organizations.

Despite these changes, religious freedom in Cuba is a distant dream. Christians of all denominations especially those worshiping in Protestant churches, have reported to international human rights organizations that they are victims of harassment and persecution by the authorities.

Christian Solidarity Worldwide's latest report on freedom of religion and belief in Cuba details 1606 separate violations between January and July 2016. Cases include the demolition and confiscation of church buildings, the destruction of church property, arbitrary detention and other forms of harassment, in particular seizure of religious leaders’ personal belongings.

There has been an unprecedented spate of church demolitions. Four large churches linked to the unregistered Apostolic Movement were destroyed by the government in central and eastern Cuba. Pastors and their families were dragged out of their homes in the very early hours of the morning.

CSW has documented nine cases of arbitrary detention in 2016, including those detained whilst their churches were being demolished. A particularly serious case involved the arrest of Revd Mario Felix Lleonart Barroso on 20 March 2016, hours before the US President Barack Obama arrived in Cuba on an official visit.

A few weeks before the Pope's visit in 1998, I interviewed a young man who was in his fourth year of studies to become a priest at the San Carlos and San Ambrosio Seminary in Havana. Like many other young people of his generation, Castor Alvarez was raised in a secular society under a régime led by a fierce atheist.

In a very candid way, he expressed his doubts about finishing his career (he had another four years to go). ‘Don't get me wrong - my doubts about pursuing this path further won't kill my faith.

'I have had to live in fear to enter the church freely and I work hard every day to overcome it. I also have to deal with people who think I've gone crazy. It's difficult, very difficult, to become a priest in this society.’

Mariusa Reyes was correspondent in Havana for The World, a radio co-production by BBC World Service – WGBH Boston and PRI.

Mariusa Reyes was correspondent in Havana for The World, a radio co-production by BBC World Service – WGBH Boston and PRI.