NEWS FOCUS Eurocrats back new European Academy of Religion

by - 7th December 2016

ISLAMIST violence in Europe is behind a revolutionary bid to reinstate religious research at the heart of the EU.

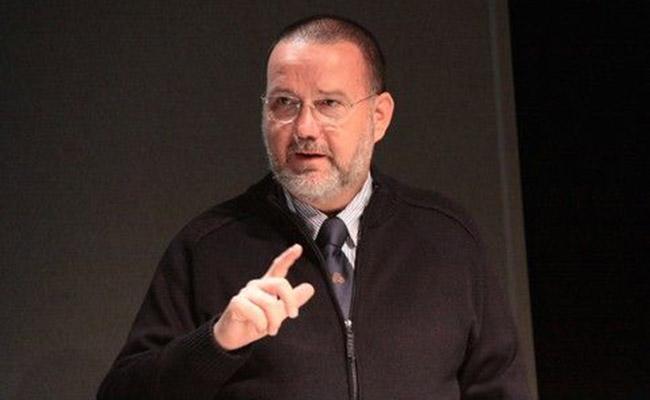

‘Everything was invited to respond to the Islamic massacres across the continent except research’, says Professor Alberto Melloni, founder of the new European Academy of Religion (EAR), speaking to Lapido after the launch in Bologna on Monday night.

Melloni, who holds the Unesco Chair in Religious Pluralism and Peace at the University of Modena-Reggio, surprised delegates with the strength of his political backing, although funding came from a private donor.

A church historian, he has done something very clever: he has sought and secured the endorsement of the most secularizing influence on the continent for a religious research body whose only rival is the American Academy.

That Carlos Moedas, European Commissioner for Innovation and Research, agreed to give the keynote address at the inaugural convention on Monday, indicates perhaps a quiet new trend in the ideological underpinning of contemporary Europe.

Melloni said: ‘Moedas was very brave. They tried to dissuade him from coming.

‘I wanted Moedas to tell these people “You belong to the field of research. You are not just fire-fighters.”

‘We treat religion like a fire that needs putting out. Research is much more than that.’

Moedas accepted Melloni’s basic hypothesis, he says. ‘We must move the issues from religious authority charged with the burden of dialogue and the burden of sentimental expression of friendship, to the demands of research, and knowledge in the belief that society will benefit.’

Gary Wilton, former Archbishop of Canterbury’s Representative in Europe, has written that there are two forms of knowledge contesting for European predominance: one based on empiricism, the other on wisdom. Though both in fact operate in similar ways, a one-sided dependence on technological empiricism has clearly won the battles of recent years, but is losing the cultural war.

Melloni’s answer is to recover what he calls ‘the unity of knowledge’ – and treat religion not, as has been the case, as a department of history, but as what he calls ‘open science’.

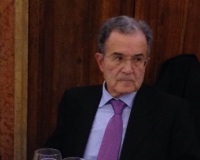

That economist Romano Prodi, former President of the European Commission spoke at the launch banquet on Sunday, reinforces the perception that religious understanding is emerging from the clammy embrace of interfaith dialogue, to be welcomed back into the serious business of ideological management in Europe.

Melloni says: ‘Knowledge is a unity and people may work on religious projects or subjects with very different epistemological paradigms, and even incompatible epistemologies. It doesn’t matter. The point is, how can I contribute to the peace in Aleppo tonight?’

European spirit

Carlos Moedas is clearly convinced enough to give it a try, and what convinced him was his brush with death at the hands of extremists in Brussels earlier this year.

Carlos Moedas is clearly convinced enough to give it a try, and what convinced him was his brush with death at the hands of extremists in Brussels earlier this year.

He told delegates: ‘Every day I think back to March 22nd and start hearing again the sound of sirens getting louder and louder and when I looked out of the window I could see that something like smoke was coming out of the commissioners’ airport. Later I could see the fall-out of the second bomb at Maalbeek station when 32 innocent people lost their lives.’

One of the dead was Patricia Rizzo – an Italian immigrant working in one of the departments of the EC.

She encapsulated for Moedas, the ‘true European spirit’.

‘From an Italian family scattered all over Europe, she worked for the European ideal side by side with 28 colleagues at the European Research Council that pushes the frontiers of science and knowledge.’

Moedas, short, slight and impassioned, was moved enough on Monday to make a second impromptu appearance at the podium, expressing his ‘pride’ at being at the event, before departing with his young retinue. He promised to ‘invest more’ at the ‘intersection of science, religion and the digital revolution.’

Fuel

Melloni denies that violence is the prompt for what may come in time to be seen as the beginnings of a deep reconstruction of European thought. Instead he says it was the uncritical use of terminology which demanded a research response. ‘To tell the violent that they are radical and the praying people that they are moderate, is like telling the Vatican themselves that they are moderates. It’s fuel on the fire.’

Such terminology is received as an insult that exacerbates the problem. Instead of regarding religion as a form of alcoholism that must be treated, he sees it as food that can nourish.

His answer is to provide the ‘radicalised boys’ not with rehab, but with a sense of the glories of their heritage. A dose of seventeenth-century Persian poetry would do more than the Prevent programme and its ilk ever could, he believes.

Stature

Melloni seeks nothing less than a revolution in our sense of our shared civilizational heritage; a response to our ‘spiritual and historical alzheimers’ as he put it. To talk simplistically about a ‘return to our Christian roots’ as if that alone were the answer, ignores the enormity of the holocaust.

So he raised Euros35,000 for the launch of the EAR under the auspices of his own foundation in Bologna.

He contacted 2,800 academic organizations and societies. Representatives of 500 responded and 400 actually attended the two-day events in Bologna, the site of arguably the world’s oldest university founded in 1088.

This connection alone is enough to excite the collective ancestral memory of the European intelligentsia, marking as it did the union of scholars for the purposes of research safe from the clutches of both church and state: the first ‘trade union’.

A city redolent of adventures in research – Galvani of galvanised steel and bioelectromagnetics; Marconi of the radio wave to name but two – seems a fitting place for this renaissance.

Envoy

Scholars of the stature of sociologist Roger Finke from Pennsylvania State University; Robert Baum who edits the Journal of African Studies; Patrick Houlihan from Oxford University and even two professors from China rubbed shoulders with senior politicians and diplomats. Martina Larkin of the World Economic Forum, and Jan Figel, Special Envoy of the European Commission for Religious Freedom, both gave powerful speeches, as did Annette Schavan, Germany’s former Federal Minister for Education and Research, and now Ambassador to the Holy See, and Stefano Manservisi, Director General of the European Commission’s Department for Overseas Development and Cooperation. Many ministers who had accepted invitations were preoccupied with Italy’s referendum, also held on Sunday.

Prodi, under whose Presidency the first 11 European nations adopted the euro, said it most clearly: ‘We have to try to understand, in the light of the new phenomena – fear, migration, disintegration, economic crisis. We have to recompose the spiritual structure of our continent.’

Prodi, under whose Presidency the first 11 European nations adopted the euro, said it most clearly: ‘We have to try to understand, in the light of the new phenomena – fear, migration, disintegration, economic crisis. We have to recompose the spiritual structure of our continent.’

Desperation? The humiliation of an intellectually bankrupt and out of touch élite? Whatever you call it – and the ‘end of the historical experiment of the Enlightenment’ was not the least surprising epithet - it is unlikely things will be quite the same again.

Said Martina Larkin: ‘We cannot leave humanity behind as the world moves forward.’