What Mandela's sacred commitment to freedom can teach Islam

by - 17th December 2013

THERE IS MORE than an journalistically opportunist link between Mandela's death and the recent nomination for Secularist of the Year to a Muslim organization one of whose founding members is Lapido Trustee Ghayasuddin Siddiqui - but you'll have to read to the end to find it.

Ghayas and I are involved in an ever-fascinating on-going conversation.

His views are a litmus test of what’s changing in the Muslim world, and part of Lapido’s value to him is, I suspect, as a conduit for news of these changes.

He tells me that as the West despairs of Islamic integration, as the ‘nuisance factor’ of burqas, university segregation, and sharia zone stickers grows more irritating for all of us, most Muslims included, against the background of 7/7 and Woolwich, the race is on to develop more credible modes of existence.

British Islam is finding what the noted Bradford Islamicist Philip Lewis calls ‘the resources within itself’ to reinvent a self capable of living harmoniously with those whom some, in other eras, and occasionally in ours, have dubbed ‘infidel’, ‘kaffir’, and targeted for jizya tax.

Hadith, the purported sayings of Muhammad, justify both shunning the enemy, and mingling with it, according to need. Muhammad after all is the source of Quran texts that talk among other things of ‘slaying the enemy wherever you find them’ (Sura 9:5 tr. Yusuf Ali).

But he was also the leader who accepted protection in the Jewish/Christian tribal city of Yathrib, the destination of the first migration or hijra. More lately, migrating to live among the infidel has also been justified in the name of mission. There’s even a new Arabic expression coined for Britain – the land of mission or ‘dar ul dawa’. While ‘the house of treaty or covenant’ is a more ancient provenance, dawa covers unease about mass economic emigration from the lands of the umma, unprecedented in history, when at least one hadith bans it.

This is where we get closer to the point about Mandela ... but wait for it a bit longer.

What is particularly poignant about developments in British Islam is what is now beginning to circulate more widely: the view that Islam is after all, a secular faith, and, as Dr Siddiqui puts it, followers should require less not more religion. Indeed, British Muslims for Secular Democracy, founded by among others, the commentator Yasmin Alibhai Brown, has just received full funding.

Religion has become an ‘obsession’ they say. Indeed.

Unrealistic

The classicist Tom Holland dismisses these attempts. ‘To insist that Muslims can have as unproblematic a relationship with secular democracy as can, say, their Anglican fellow citizens is unrealistic – not to mention unfair on Muslims themselves. To imagine that Islam, with a gentle nudge here and a little push there, can be transformed into a kind of Church of England with hijabs – a Mosque of England, perhaps – is pure fantasy. The gap between liberalism and a faith that has repeatedly shown itself uncomfortable with many of liberalism’s most basic presumptions cannot simply be wished away.’

But it is being wished.

A brochure from the brand new organization New Horizons has just landed on my desk. It is a business proposal, beautifully worked through, with images of a blond mother and child, a Scottish loch, and a logo of a bird in flight – which alas, looks unfortunately like a hawk.

The brochure says bravely: ‘New Horizons is a forward-looking organization that works for reform in Muslim thought and practice. It is inspired by Islamic values and spirituality and speaks from within the Islamic tradition, but for the benefit of all people. Our vision is of a society where relations between Muslims and their fellow citizens are strong and healthy and where Islam feels at home, rooted in its British context . . . It is not a “by Muslims, for Muslims” type of organization, but works for the benefit of all people.’

What is the link between this Islam, and the Islam that is wiping out whole villages of Christians in Syria, or Shi’i in Iraq? Is Islam simply ‘a broad church’ accommodating theological difference with infinite elasticity – or is there in fact a solid core? The debate is becoming more robust and that in itself has to be applauded. More people are getting the hang of debating these things.

The Council for Ex-Muslims in Britain is also struggling for a secularity that makes ‘religion’ itself redundant, and indeed New Atheists Richard Dawkins and Anthony Grayling not only heartily endorse them, but addressed the launch.

Post-Christian

But welcome as these initiatives are, they risk obscuring what makes a ‘secular society’ possible.

Once again, it was the atheist columnist Matthew Parris, who wrote last week: ‘Christianity is mankind’s most serviceable road to atheism’ — meaning that Christianity teaches people to be free of crippling superstitions and religious laws.

‘I think Christianity is on the side of the free spirit', he writes. 'In teaching a direct and unmediated link between the individual and God, it can liberate, releasing people from fear (as I’ve seen missionaries do), freeing people from the weight of their own culture, empowering them to stand up for themselves, to love and to respect themselves.

'Christianity can smash the metaphysics that entrap cultures’, he concludes. He is convinced that a Christian foundation is essential for a secular society.

Holland wrote similarly in the New Statesman: ‘… though contemporary secularism may like to think of itself as being post-Christian, it remains no less the legacy of the west’s ancestral faith for all that. Its core presumptions – that religion should not aim to provide people with a political blueprint, that church should be separate from state, and that laws should express popular sovereignty rather than the dictates of a holy book – are all of them, ironically enough, shaped by the teachings of the New Testament.’

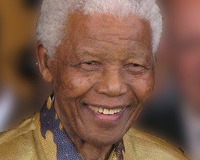

The world here and now, the present age (saeculum) is what Christian belief has it that God died to save. ‘ . . . for God so loved the world that he gave his only Son …not to condemn the world, but to save it.’ (John 3:16). Not just a South Africa fit for all as Mandela, who emerged a Christian from his prison cell, said, but a world fit for all.

Jesus of Nazareth, the only faith founder in history who was worshipped by his contemporaries, and who, as evidenced even in the Talmud, worked miracles, hated more than anything religion and traditions that oppressed people.

He railed more against religion than sin. In reference to cruel purity and Sabbath laws he said, ‘A man is not defiled by what goes into his mouth, but by what comes out of it.’

In the famous phrase of Kenneth Cragg, recently deceased former Bishop of Jerusalem, God hated religion so much, he rendered even himself ‘negligible’. The ‘negligibility of God’, means societies that deny him are possible.

It is in the licensed movement of individuals from rebellion and dissent through to the dawning of enlightenment that society becomes possible. It is in the interstices between licit doubt and oppressive certainty that human beings grow up and flourish.

But when the secular becomes itself the goal, setting itself up as a religion with no transcendent reference, it not only loses its semantic meaning, it simply self-destructs. First books, then people, burn, as Anne Applebaum shows in her Iron Curtain: the Destruction of Eastern Europe which is the terrifying and too little told story of soviet anti-Christian socialism and the slaughters of 30 million people that began with priests and believers.

Lamin Sanneh the Yale history don and Senegalese scholar wrote: ‘Where the secular realm seeks to ‘shorten the odds on the long-range, timeless truths of religion, [it] ends up removing the safety barrier against political absolutization’ (Faith and Power: Christianity and Islam in ‘Secular’ Britain 1998, p:72).

Islam contains within itself, more than any religion, the ability to totalize itself.

The instinct for domination lurks amid the holiest texts. ‘The best people,’ Muhammad is said to have declared, ‘are my generation, then those who follow them, then those who follow them.’ Thus, it was not merely the primal Islamic state of Medina that was worthy of emulation, but also the colossal empire founded under the rashidun, the ‘rightly guided’ successors of the Prophet, the first four caliphs.

For Muslims, unlike Christians, it does make sense to talk of a political golden age – and to dream of seeing it restored.

Solidarity

Muslims who believe that Islam is at core secular have in fact lost their faith, but not their visceral ethnic solidarity or even yearning for God. And that’s OK in secular Britain. Cultural Christians who go to church only at Christmas, lapsed Catholics who turn out to see the Pope, secular Jews who dispense with the seder and marry 'out' … all are an accommodation to secularism.

When Muslims tell you they no longer follow shariah, or attend the mosque, or send their children to the madrassa, because ‘it is not education’, or that they do not even love the Qur’an except in recitation, they have lost their faith. They are sheltering within the civic space created by a religion they deny – the Christian religion – and are undoubtedly being the more British for it.

They, like the rest of secular Britain, want the benefits that Christian sacrifice and struggle have won over the painful centuries, with none of the Cross. And that is their entitlement.

But make no mistake. Only a sacred commitment to freedom can motivate a struggle for the freedom of others, as Nelson Mandela, who emerged from his prison cell a Christian committed to reconciliation, showed us.

And this is the point.

Only a religious commitment to the good of all can withstand the onslaughts of political ambition and the overweening State. That was the commitment demonstrated by the God who came down at Christmas and entrusted himself to a world that did not know him, and for which he died in agony.

The paradox is that it was the Protestant reformers who liberated us from religion’s chains and died for freedom of conscience, who laid the foundations of a secular society fit for all - including Muslims.

- Log in to post comments